You’re finally done with your design project, you go to save your file, and suddenly you’re bombarded with over a dozen possible image file types to choose from. It can be a bewildering experience if you’re not sure what you’re doing or the difference between them, but we’re here to demystify the process for you by helping you understand the cold, hard truth:

There are only a handful of image formats that really matter.

Now, before you die of shock and outrage, we’ll fully admit—there wouldn’t be that many file types to choose from if they didn’t each serve a particular purpose. But a lot of them are specialized file types that you’ll never use, especially when designing for print.

So with that bit of unpleasantness out of the way, let’s get down to figuring out the image file types that matter most.

Raster vs. vector images

To fully understand the difference between the image file types available to you, you first have to know the difference between vector file formats and raster file formats.

Raster images are created with pixels, and can be anything from simple illustrations to complex images like photographs.

Because raster images are made from a fixed set of pixels, they experience a loss of quality whenever resized, especially when you’re trying to make them larger. Raster images are typically used as the final product—something that is ready to be sent to the printer or published online.

Vector images aren’t exactly images at all—they’re like mathematical formulas that communicate directly with your computer to tell it what kind of shapes to render. Because of this, vector images can easily be changed or resized without any loss in quality, since the formula simply adjusts to render a new illustration at the desired size.

Vectors are typically used to create illustrations, text and logos, but they can’t handle complex images such as photographs. Vectors are typically used as working files (which are later converted to raster images for the web), but they can also be used as print-ready artwork.

Know your file types

Classifying the common file types you see in print and web design takes more than just dividing them up between raster and vector images. Both raster and vector file types are blanket terms that envelope a wide spectrum of different file types with different functions, purposes, benefits, advantages and disadvantages.

Raster formats

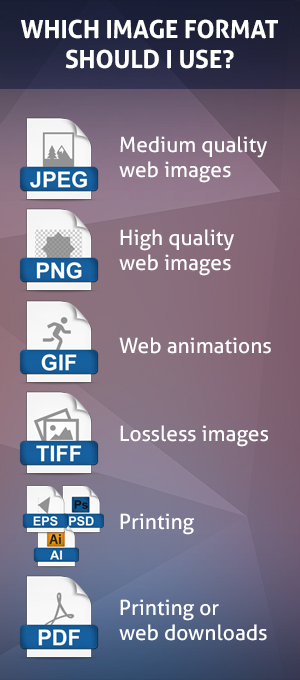

JPEG

Okay, we can admit it, maybe we were a bit unfair when we said that JPEGs suck. They don’t always suck, they just aren’t the best choice for printing. The JPG file format uses lossy compression, which is great when you want to reduce image file size, but isn’t high enough quality to look good in print and definitely shouldn’t be used for a logo design.

Okay, we can admit it, maybe we were a bit unfair when we said that JPEGs suck. They don’t always suck, they just aren’t the best choice for printing. The JPG file format uses lossy compression, which is great when you want to reduce image file size, but isn’t high enough quality to look good in print and definitely shouldn’t be used for a logo design.

Because of this low file size, JPEGs are primarily used in web design, as the format allows web pages to load faster. The JPG format is also used heavily in digital photography, since the loss in quality isn’t as noticeable and the low file size means being able to store more photographs on a memory card or hard drive.

Thanks to this, JPG has become somewhat of a “default” file type for those outside of the design industry. In fact, you’ll probably run into clients with tragically grainy JPEG logos or those who prefer to work exclusively in this design format because it’s familiar to them. Do your best to steer them towards other file formats better suited for their needs.

GIF

Nobody can seem to land on a pronunciation for this file format. Designers have been using a hard “G” sound at the beginning of the word for years, though its inventor Steve Wilhite says it’s pronounced “jif” like the peanut butter brand. Either way, the acronym stands for Graphics Interchange Format and it’s a file type used primarily in web design.

Nobody can seem to land on a pronunciation for this file format. Designers have been using a hard “G” sound at the beginning of the word for years, though its inventor Steve Wilhite says it’s pronounced “jif” like the peanut butter brand. Either way, the acronym stands for Graphics Interchange Format and it’s a file type used primarily in web design.

The biggest thing GIFs have going for them (in comparison to other web image formats) are their ability to be animated; you’ve probably seen plenty of them in the form of funny cat memes and reaction GIFs.

GIFs can also handle transparencies and maintain a low file size. However, low is a relative term here—the more colors you use, the larger your GIF will be, which doesn’t really make it a good format for photography (unless you need it to be animated for some reason). Even then, you have to be aware of how many frames you’re adding and how big the canvas is, as both of these can contribute to high file size and slow load times.

PNG

The PNG format combines qualities of JPG and GIF, but it’s also in a league of its own. Like JPGs, PNGs are great for detailed images like photographs, but they’re also capable of producing higher quality images than JPG.

The PNG format combines qualities of JPG and GIF, but it’s also in a league of its own. Like JPGs, PNGs are great for detailed images like photographs, but they’re also capable of producing higher quality images than JPG.

Like a GIF, PNG can include transparencies, so it’s a boon to digital designers who want to use transparent elements but don’t want to sacrifice image quality.

The biggest downside to files with a .PNG extension is that the high image quality comes at the price of image size, so too many of them can slow down a website’s load time. They’re best when used sparingly on the elements that absolutely need better quality than what a JPEG or GIF can handle (such as high resolution logos). PNG is also a raster image type, so you’ll lose some of that quality if you need to resize your graphics.

TIFF

TIFF (or sometimes TIF) is a lossless file format, which means nothing is lost when the file is saved and compressed. TIFFs also have the capacity to support layers.

TIFF (or sometimes TIF) is a lossless file format, which means nothing is lost when the file is saved and compressed. TIFFs also have the capacity to support layers.

For this reason, it’s common to see TIFF referred to as the “print-ready” image format, though many printers prefer to work with native file types such as AI and PSD.

The TIFF file format is big—too big to ever be used in web design. It’s likely to scare your less experienced clients, too, so be prepared to have copies of your design in formats that they’lll understand.

PSD

PSD is Adobe Photoshop’s native format, meaning files of this type can be edited non-destructively in Photoshop.

PSD is Adobe Photoshop’s native format, meaning files of this type can be edited non-destructively in Photoshop.

You’d never embed a PSD on a web page and it’s not a great choice for sending clients previews of your design (unless they’re familiar with Photoshop), but it’s a great format for sending to printers and fellow designers.

Vector formats

EPS

EPS is a standard vector file format—which means it’s basically just a bunch of formulas and numbers that create a vector illustration. It’s an essential file format for any type of design element that might need to be resized, including logos.

EPS is a standard vector file format—which means it’s basically just a bunch of formulas and numbers that create a vector illustration. It’s an essential file format for any type of design element that might need to be resized, including logos.

The EPS file format is print-ready, but it’s not something you’d ever use directly in web design. Instead, EPS design elements are usually converted to PNG, JPG or GIF for use on the web.

Design elements saved as an EPS can be loaded into any design program that supports vector illustration and can be resized or altered. Therefore, EPS is something you typically only share between your client, printer or other designers working on the project—anyone you might want to have the power to manipulate the raw elements of your design.

AI

The AI file type is like EPS’s Adobe-branded cousin—both are vector file types, but AI is Adobe Illustrator’s native format. Anytime you edit, save, or open an ongoing project in Illustrator, you’re working with an AI file.

The AI file type is like EPS’s Adobe-branded cousin—both are vector file types, but AI is Adobe Illustrator’s native format. Anytime you edit, save, or open an ongoing project in Illustrator, you’re working with an AI file.

An AI file can’t be embedded on the web and it’s not something you’d likely share with your client—it’s likely make their head spin unless they’re a tech savvy Adobe geek. But it’s good for internal use and sharing with your printer.

Other

Adobe’s PDF file format is the best of both worlds—good for both digital and print distribution. It’s a file format that will please both your client and your printer, while giving you the option to share directly with the audience as well. It’s also quite flexible, especially when you understand how to edit a PDF. PDFs may contain either raster or vector images, or even a bit of both.

Adobe’s PDF file format is the best of both worlds—good for both digital and print distribution. It’s a file format that will please both your client and your printer, while giving you the option to share directly with the audience as well. It’s also quite flexible, especially when you understand how to edit a PDF. PDFs may contain either raster or vector images, or even a bit of both.

You’ll hardly ever embed a PDF directly on a website, but you can offer it as a downloadable file that can be read on any PDF reader. It’s also a good file format for sending to your client as a preview of what their final design will look like.

However, this only really works for book-shaped documents like brochures or pamphlets. For print designs that have to be cut and assembled (like presentation folders), you’re better off using a mockup template to show your clients what the final design will look like.

Converting to different file types

During the creation of just one print design project, you could find yourself juggling multiple file types at once. Maybe you have JPG photographs and an EPS logo and the entire project is being built in Photoshop as a PSD file.

This is a good thing—every image file type has its own strengths, and a savvy designer utilizes these strengths on a case-by-case basis, choosing the best file type for the job. You’re likely to have multiple file types of a single design element; a company logo might have an EPS master copy, a PNG web version, and an animated GIF for special occasions.

You can save and convert practically any image file type you’ll ever need from within Photoshop or Illustrator. However, when you’re converting one file type to another, there are a few things to keep in mind. For starters, saving a low-resolution image as a high-resolution file type will not magically improve the image quality—but you better believe that saving a high-res image as a low-res file type will make it look worse.

Photoshop actually comes with its own built-in image file type converter: it’s called the Image Processor. Check out the Adobe site for info about how to quickly convert multiple files at once.

Converting from a vector to a raster file typeis easy—you just save the image as the raster image file type of your choosing. However, doing so will compress the vector into pixels, which means you won’t be able to manipulate it or resize it anymore, so it’s always a good idea to save it as a separate copy.

Converting from raster to vector is an entirely different beast altogether. There’s no easy way to convert the pixels of a raster image into the formulas that make up a vector image. The best you can do is essentially trace the image to recreate it as a vector shape.